How Tribes and Conservation Partners are Bringing Swift Foxes Back to Their Historic Range

In the midst of the pandemic, as the story goes, a team set out to bring swift foxes back to a land they had disappeared from more than 50 years ago. Swift fox populations declined dramatically from the late 1880s through the 1960s. Estimates show that they now occupy 44% of their former range in the U.S. and just 3% in Canada.

Our team at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute is collaborating with Fort Belknap Indian Community on a five-year swift fox reintroduction project. Together, and with support from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Defenders of Wildlife, American Prairie Reserve, and World Wildlife Fund, we are bringing swift foxes back to Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Montana.

Adult swift foxes weigh about 5 pounds, making them the smallest members of mainland North America’s canid family, which includes wolves, foxes and coyotes. They live on prairies with short, native grasses but can also be found in areas dominated by sagebrush or on cultivated lands. Today, they are divided into two populations, northern and southern, separated by a gap of about 200 miles.

Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, located in the homeland of the A’aniiih and Nakota tribes, is situated within that gap. Connecting the northern and southern populations will allow swift foxes to move throughout the landscape, exchange genes through breeding and develop healthier, more resilient populations.

For two years, we carefully planned the reintroduction, but nothing prepared me to try to conduct this process during a COVID-19 pandemic. I had to add a set of safety restrictions on top of the trapping procedures to keep everyone safe and healthy. On Aug. 27, 2020, our team headed to Wyoming to begin trapping swift foxes and translocating them to the reservation.

We scouted a few sites before choosing to trap at Shirley Basin in Carbon County, Wyoming. Shirley Basin is a high-elevation grassland that is undeveloped, lightly grazed by cattle and extremely beautiful. The habitat is different from our field sites in Montana. There are many ground-dwelling critters, like white-tailed prairie dogs, and hundreds of pronghorns running around (Did you know that there are more pronghorns than people in Wyoming?).

Swift foxes are so common around this area that, unfortunately, the first two we saw were roadkill. We spotted them on our drive to the Wildlife Research Station at Sybille, where we kept the swift foxes we caught until it was time to move them to the reservation. The research station is a historic site. Black-footed ferrets (once thought to be extinct) were first bred there in 1987 after a small group of surviving ferrets was discovered in Meeteetse, Wyoming, six years earlier. Today, facilities across the country breed black-footed ferrets for reintroduction.

We were fortunate to have access to the station, as well as the support of veterinarians and wildlife handlers from the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. On the afternoon of Aug. 31, our team met near the Wyoming Fish and Game Office in Laramie, Wyoming, to get ready for our first night of trapping. We split into four “pods,” or small teams. Each pod was responsible for a set of live box traps, which we used to catch the foxes. Live box traps are made of wire and have doors with bait. If a fox enters the trap to retrieve the bait, the door closes, securing the fox safely inside.

We prepared two trailers filled with box traps and set off for Shirley Basin, about an hour’s drive from Laramie. When we arrived, our lead trapper, Jessica Alexander, explained the proper trapping techniques. We would set up the traps in places where swift foxes were likely to be moving around, and arrange them so the foxes would be comfortable entering the traps. Our main bait was a mixture of sardines and bacon (a winning combo!).

I assigned each pod an area to set their traps and gave them a radio for communication. Shirley Basin is very remote with little cell coverage, so we set up a rendezvous point and agreed on a time to meet back up later that night. Then, we were off.

The first evening was chilly with strong winds, something Shirley Basin is known for. We returned to our rendezvous point after dark, when each pod’s traps were set and ready, and headed back to Laramie to get some rest. I was too excited to sleep and kept waking up to check the clock. At 3:30 a.m., my alarm finally went off. It was time to check the traps. We hopped into four trucks and returned to Shirley Basin, where each team set out to check their traps.

There was no fox in my first trap. Nothing in the second. Trapping is difficult, and this was not my first rodeo, so my expectations were low. Nothing in trap 15, 16 or 17. Though I know the name of this game, I had started to get disappointed. As I headed toward my last set of traps, I got a call on the radio. It was my Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute colleague, Andy Boyce: “Hila, come and get your fox!”

I caught one! My last set of traps was very close to Andy’s, and he had arrived there first. There was one fox in my trap and two more in Andy’s traps – a mom and two kits. Catching three foxes on our first night was lucky. Once everyone had returned to the rendezvous point, we moved the foxes into their transport crates.

We drove back to Sybille Research Station, where we met wildlife veterinarians Drs. Samantha Aleen and Peach VanWick of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. They examined each fox and screened for several diseases to make sure the foxes were good candidates for translocation to Fort Belknap Indian Reservation.

Lead trapper Jessica Alexander (right) gently restrains a female swift fox while Peach VanWick (left), wildlife veterinarian and manager of Sybille Research Station, examines the fox.

Trapping wildlife is rigorous work. We needed to be focused 100% of the time and didn’t get much sleep. The weather was not on our side either. After all, it’s Wyoming and conditions are unpredictable. We arrived to a Red Flag Warning — strong winds and temperatures over 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Before our 10 days of trapping were up, temperatures had dropped below freezing, and we had 8 inches of snow! Luckily, we had all brought along summer and winter gear. Coming from Montana, where fall weather also fluctuates a lot, we were prepared for possible extreme weather.

We kept up our trapping routine each evening, and moved our box traps to different locations every few nights. My pod caught a record seven foxes one night, but most nights we returned to the research station with about three foxes. After 10 days, we had 27 swift foxes ready to move to the reservation.

We transferred the foxes from Wyoming to Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Montana, where we placed them in 5-by-5-foot, fenced in areas, called soft-release pens. The pens allowed the foxes to move around safely for a few days while getting used to their new surroundings. In each pen, we paired a male and female fox that had been caught close together. One pen held three kits, or young foxes, from the same litter.

We carefully selected a location for each pen based on habitat assessments we had conducted earlier, and set them up over large, empty prairie dog burrows. We hoped the foxes would use these burrows as their new dens. Swift foxes use dens year-round and rely on them to escape from predators. We also placed empty crates above ground, so the foxes would still have a place to hide, even if they didn’t like the burrows.

The Gros Ventre and Assiniboine Tribes held a ceremony to celebrate the swift fox’s return to Fort Belknap Indian Reservation and this important step toward restoring balance to the ecosystem. They held a small gathering outside to welcome the little critters. I felt honored to be present and for the opportunity to work with this amazing community.

The foxes did well in the soft-release pens, seemed very calm and ate a lot of the bison meat provided by the tribes. In the wild, swift foxes scavenge and prey on insects and small mammals, mostly rodents. Some of the foxes dug their way out of the pens, which we expected, and we let the others go after five days.

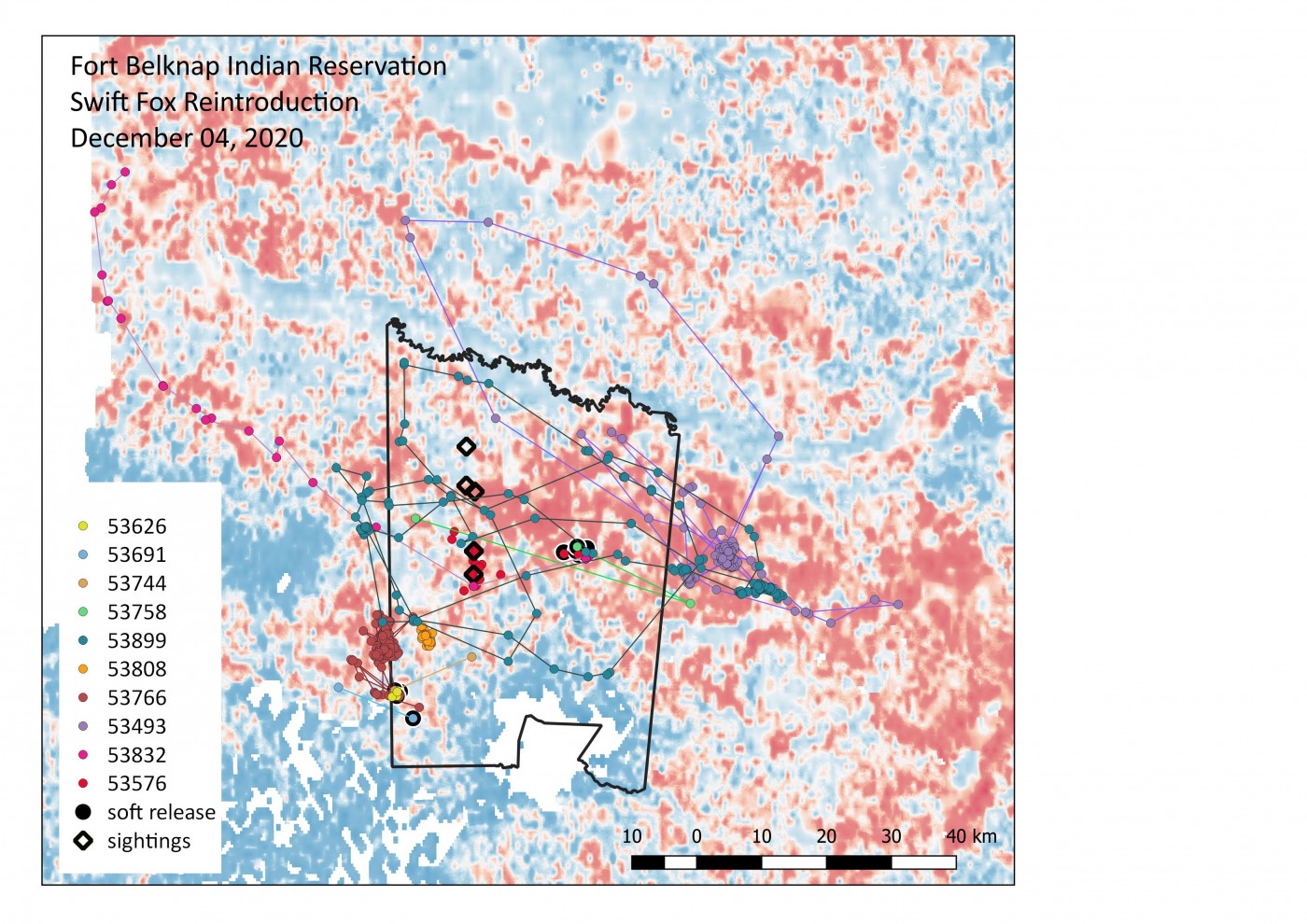

Each fox was equipped with a lightweight LTE-GPS collar that collects its location three times a night. The locations are stored on the collars and sent to us when the foxes wander within cell service range. The collars should last up to 18 months and will help us learn more about the habitats the foxes select, their home ranges and their survival rates.

It has been three months since we released the swift foxes. They seem to be living in areas that we predicted would be good habitats, which is an indication that things are on the right track. The GPS collars show that some foxes have stayed put, while others have traveled long distances of 50 miles or more.

Like every field project, and especially when reintroducing a species, we will continue to evaluate the success of our efforts, monitor the animals and adapt our protocols. Now that winter is here, it is going to get tough for the foxes. Not all of them will make it, but that is the natural fate of wildlife. We hope that many of them will survive to mate next spring, and we are impatiently waiting to find the first litter of swift fox kits.