Science To The Rescue In The #Fightforfrogs

Nearly one-third of all amphibian species globally are at risk of going extinct. While the global amphibian crisis is the result of habitat loss, climate change and pollution, the deadly amphibian chytrid fungus plays a large role in the frogs' disappearances. In the fight for frogs, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute biologist Brian Gratwicke and partners are making strides in finding a cure for chytridiomycosis disease with the help of probiotics.

This story appears in the July 2016 issue of Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute News. Want science delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for the e-newsletter here.

When Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) scientist Brian Gratwicke started the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project (Rescue Project) with partners in 2009, it was a mad dash to find and collect frogs representing the very last best hope for their species, rapidly vanishing at the hands of an amphibian chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis or "Bd") that causes a disease called chytridiomycosis.

If that was the opening chapter of the Rescue Project’s story, seven years later the story reads like a manuscript for one of the most successful conservation projects to date.

Today the Rescue Project has provided a stable safe haven for 12 of the most imperiled Panamanian frog species, requiring keepers to learn the complex husbandry, behavior and reproductive physiology unique to each individual species. In the meantime, rescue project scientists are making strides in developing and refining assisted reproduction protocols, while also conducting experiments in a resolute search for a cure for Bd.

"We are entering a new phase," Gratwicke says. "We’ve brought together some of the world's leading animal husbandry experts, veterinarians, reproductive biologists, disease ecologists and herpetologists. With all of the talented scientific minds working on this one, we have great hope that we may someday be able to return these species safely to their home in the wild."

Searching for a Cure

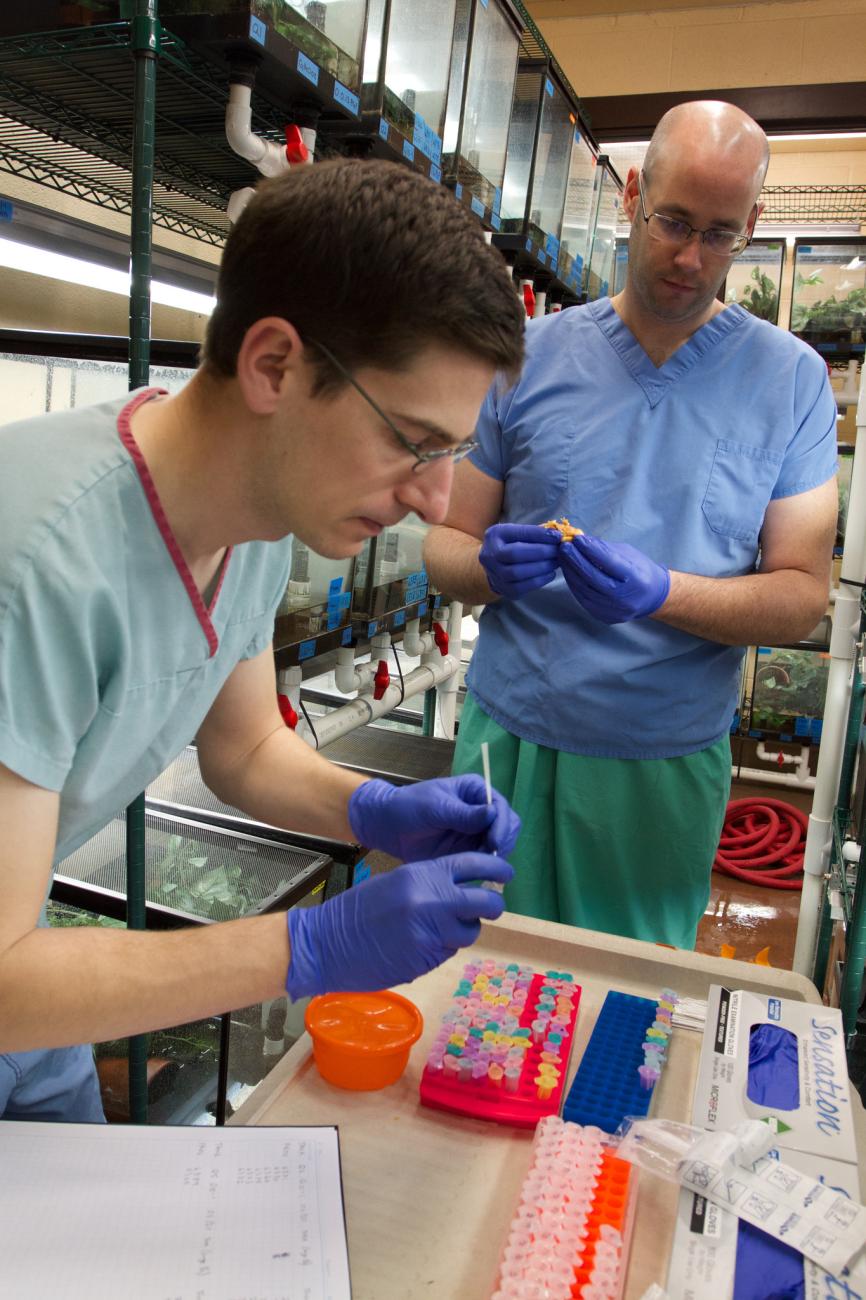

Things in Matt Becker's lab can sometimes get a bit... strange. Take, for instance, an experiment the SCBI postdoctoral researcher conducted a year ago with unexpected results. Becker's research focuses on the use of probiotics—or beneficial bacteria—to help frogs fight off chytrid. Last year, Becker applied five different probiotics with anti-fungal properties to the skin of five groups of Panamanian golden frogs, hoping to discover which probiotic effectively shields them against the pathogen.

What he found surprised him. In past experiments, the probiotics were ineffective and all of the frogs died after the researchers infected them with chytrid. This time, about 25 percent of the individuals survived. And those surviving frogs didn't come from just one group with one kind of probiotics, but from every group, even the one that had been infected with chytrid without a probiotic protectant.

So Becker and Gratwicke needed to determine what the frogs had in common to help them fight the disease. They started by looking at the frogs' microbial community, or the complex community of bacteria on the skin. All of the frogs that survived had a greater abundance of specific bacteria on their skin.

In June of this year, the team launched a new experiment, this time using frogs from the Species Survival Plan collection at the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore that have similar abundances and types of bacteria as those that survived last year. The researchers have given the frogs a cocktail of eight bacteria that seem to strongly ward off chytrid.

"At the start of every experiment, you're really optimistic," says Becker, who has been working on golden frog probiotics since 2007. "It’s been a great journey and we’re really learning a lot about golden frogs and how chytrid affects these guys. Every little bit of information really goes a long way for the conservation of these frogs and similar species."

For the first time during a probiotics study on frogs, the researchers will also be looking at the gene expression—or combination of genes in an individual frog that gets turned on or turned off—while the frog mounts an immune response to fight off chytrid.

"We're throwing everything we've got at this," Becker says. "We want to be able to use these tools to determine which frogs in the overall captive population share those same strengths—either their microbial community or gene expression—that keep them alive. There are so many questions we need to answer, but through the scientific process, we’re getting there."

Frogs for the Future

While Becker is focused on getting frogs safely back into the wild, this goal is only possible if there are actually future generations of frogs to release into the wild. That's where Smithsonian researcher and Panamanian native, Gina Della Togna, comes in.

Della Togna is working on a number of complex assisted reproduction techniques for Panamanian frog species. She is the first scientist to develop protocols for extracting and freezing sperm from the Panamanian golden frog—a species that is extinct in the wild and a cultural icon in her home country. Scientists could someday use the sperm to infuse populations with additional genetic diversity, which is key to a species' overall health.

"When we started, we didn’t know anything about anything," Della Togna says. "We needed to learn which hormones at what concentrations to use, how to keep the sperm alive long enough to freeze it and the best techniques to freeze it so that the sperm is viable when we thaw it, even years later. It was a challenge, but I love a good challenge."

Now Della Togna is working on developing similar protocol for other Rescue Project species, including the mountain harlequin frog, Pirre harlequin frog, variable harlequin frog, limosa harlequin frog and the rusty robber frog. In the future, she plans to get out into the field to capture genetic lineages from frogs in the wild. As she continues to perfect these protocols, Della Togna also aims to collect eggs from female Panamanian golden frogs to use for artificial fertilization with the frozen sperm. And most recently in Panama, she successfully applied a hormone treatment to help six pairs of the limosa harlequin frog and Pirre harlequin frogs breed that hadn't laid eggs before.

"Breeding frogs is the fundamental step to sustaining captive populations and growing the numbers for release trials," Gratwicke says. "Gina’s work is of huge value to us because we have some very challenging species to breed. Hormone dosing may help us to get them to cycle reproductively, even if we can’t figure out the external reproduction cues."

For Della Togna, Gratwicke and Becker, the goal is the same: to give these unique species a fighting chance against chytrid.

"If these frogs go extinct, nothing can replace them," Della Togna says. "They are important to the ecosystem and essential to our planet’s equilibrium. There's no doubt that we're responsible for getting them back to where they belong."

Related Species: