Searching for the Invisible, Invincible Peruvian Tern

Esta historia esta disponible en español aquí.

On Peru’s pacific coastline, where desert meets sea, lives one of the least studied and most at-risk birds: the Peruvian tern, known locally as “gaviotin Peruano” (Sternula lorata). The tern is nearly invisible in its native habitat, which looks more like a moonscape than anything you would expect to find on Earth. Its desert camouflage makes it almost impossible for scientists to track, but that’s exactly what our team set out to do. It would take us four months to survey more than 1,851 acres, battling sandstorms, stifling heat and impossible landscapes inside Paracas National Reserve — terrain that the Peruvian tern has mastered.

Peruvian terns are part of a small group of terns (Sternula) that are slender, with long beaks and short legs. They have white feathers with black “caps” that look like masks, and they lay their eggs in shallow depressions in the bare ground. They are found in Paracas National Reserve, Peru’s oldest marine protected area, where reports suggest they began nesting as early as 1920. One hundred years later, the Reserve treasures the largest nesting colony in the country.

But Peruvian terns are on a path toward extinction, and the population in Paracas is no exception. According to the IUCN’s Red List of Endangered Species, Peruvian tern populations are decreasing. A 2018 survey of Paracas’ nonbreeding terns reported fewer individuals than in the past, and the last survey of the Reserve’s breeding population was conducted nearly a decade ago. Our team wanted to find out how many terns still nest in the park and what threats they face. Locating them would be the hardest part.

Paracas National Reserve is home to a myriad of species of all sizes, from sea lions and seahorses to foxes and geckos. Seabirds are common; many are residents and many more are migrants. Wildlife thrives in the intertidal zone — the zone where the Pacific Ocean meets the shoreline — but it’s a different story on land. The extremely dry landscape makes this habitat nearly impossible to occupy. “Paracas” means “sand rain” in Quechua, the Andean native language, and when it “rains,” it pours. During the sandstorm season, sustained winds of up to 62 mph (100 kph) unroll a thick curtain of sand. This extreme environment is unwelcoming to humans, but it’s an oasis for the Peruvian tern.

How has the tern thrived in this harsh environment? By being invisible. Although we are still learning about this species (there are just four studies on Peruvian populations), we know one thing: they are masters of matching their environment. When the wind blows, terns crouch close to the ground to disappear. They build nests that are nearly impossible for outsiders to spot and adorn them with tiny stones, shells and bones. These visual cues help the birds locate their nests in the homogeneous landscape. Masters of disguise, even their eggs and chicks are the same color pattern as the ground. It’s like the terns wear invisibility cloaks.

To find them, we would need help. So, our team at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute partnered with a private company, Terminal Portuario Paracas (TPP). TPP is leading the expansion of General San Martin Port Terminal, a port in Peru for the import and export of goods. The road to the port is also the only road that leads to an area where the Peruvian tern has historically nested. The paved and busy road was built in the 1950s before Paracas National Reserve existed.

Thus, the terns still live in the area, and we don’t know if the increased activity from the port will affect them. In October 2019, with the sandstorm season officially over, we established our base camp in El Chaco, the last urban area before the desert landscapes of the Reserve. Our goal was to cover 1,851 acres in just four months before the end of the reproductive season. We would study tern flight patterns and comb the area for nests.

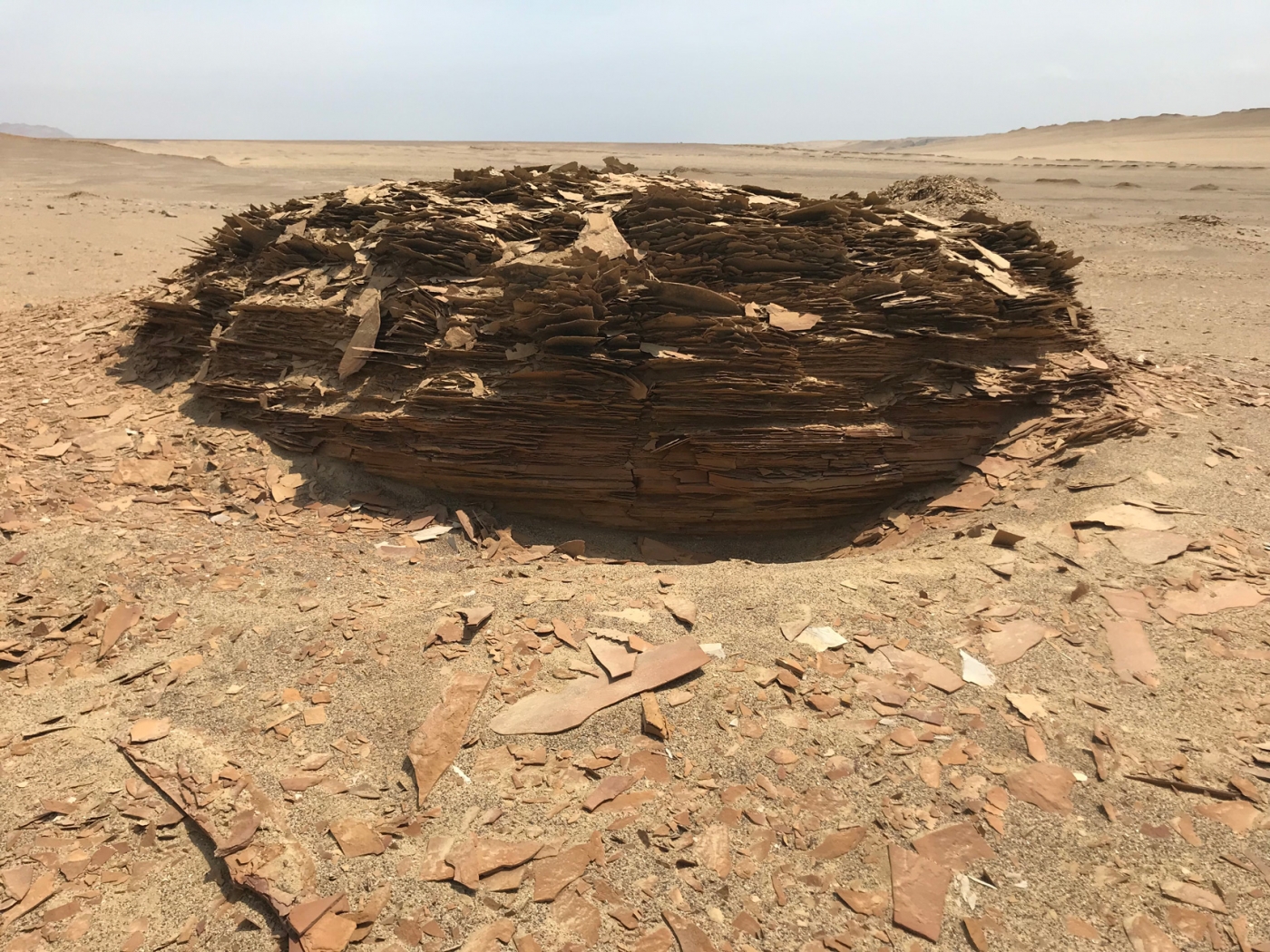

At 6 a.m. on Dec. 2, 2019, at the onset of the Austral summer, we headed into the already hot desert. One hour later, we were in the middle of nowhere feeling more on the moon than on Earth. The terrain changed abruptly from hollows to hills, with bizarre sculptures that resembled giant puff pastries.

Between the dunes and hills of the northern side of the park is Cequion Bay — the largest flat terrain in the Reserve. It took us six hours to find the first active nest. Trained eyes and determination helped us detect the subtle circular depression in the ground. Inside were two tiny eggs, each with spotted coloration that matched the ground.

Our next challenge was to set up sound recorders and camera traps. We deployed our recorders along the road, at increasing distances from the road, and near active nests. The lifespan of each recorder was about 12 days. They were set to record one minute of sound every 10 minutes until their batteries ran out. Our camera traps were camouflaged under sand and gravel. We placed them about 9 feet from nests located near the road, to capture both the adult terns and the road traffic. The cameras were set to take a picture every 5 seconds until the batteries ran out.

It might be difficult to imagine the full scope of our work, so let’s compare it to something most people are familiar with: football (soccer).

- Between December 2019 and March 2020, we inspected the equivalent of 1,050 soccer fields in search of nests.

- We analyzed 40,000 1-minute sound recordings, the equivalent of 444 soccer games.

- We analyzed 500,000 images from camera traps, which is about the number of photos a professional photographer would capture during 143 of the most amazing soccer games.

Between the dunes and hills of the northern side of Paracas National Reserve is Cequion Bay — the largest flat terrain in the part of the Reserve.

This enormous effort was well worth it. We suspect that, after 70 years, Peruvian terns have learned to manage the road that disrupted and likely fragmented their habitat. We identified 20 active nests and 26 past activities, including two new nesting areas adjacent to the road that were previously unreported. Noise can have a major impact on bird populations, so the fact that some terns are still nesting near the road is encouraging for their long-term conservation. It tells us that they are both resilient and adaptable.

The sound recorders and cameras told similar stories. Images showed adult terns undaunted by road traffic. Sounds near the road were loud and covered a large sound spectrum, but about 656 feet (200 meters) away, the road noise was nearly undetectable. Most of the nests we found were located far from the road, where our sound recorders detected only the birds’ morning calls.

When we started our study, we wondered what could threaten this tiny bird that looks like an avian Batman with its “mask” of black feathers and has evolved to survive desert predators and sandstorms alike. Surveying such a big area gave us unexpected information that portrays a complex scenario for their conservation. Inside the park, we found lots of garbage, dogs tracks and illegal roads. The garbage pollutes the terns’ nesting habitat, but dog tracks and illegal roads are another story. Domestic animals are predators of wildlife and could pose a threat to the terns.

A Peruvian tern nest containing two tiny eggs, each with spotted coloration that matches the ground.

Illegal roads were the most unexpected and worrying discovery. Their existence is subtle, but this landscape has memory (and a particularly good one for tracks made by cars). No matter how strongly winds blow, the roads are still visible. We mapped each one and saw a tangle of existing illegal roads traversing the terns’ nesting area, and two new roads appeared during our study. With few paved roads, it’s tempting for park visitors to take old short-cuts or make new ones. The terns cannot avoid the destructive effects of visitors searching for hidden beaches or exclusive sunset views, or local fishermen looking for the daily catch.

At the beginning of September 2020, after wrapping up months of data analyses, we stood in front of the Peruvian environmental authorities to tell the evidence-based story of Peruvian terns, share our findings, and make recommendations for their long-term conservation. Our research made the Peruvian tern visible. Peru and Chile are now joining forces to recover the tern’s depleted populations. With our data and lessons learned, we are developing an ambitious, integrated monitoring program to stop the Peruvian tern from taking a one-way detour to extinction. As we work on this rescue plan, I am reminded of the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute’s mission: We save species. We do. And for this work, we must try to be just like the Peruvian tern, invincible.