Bringing DNA Metabarcoding to Lebanon's Cedar Forests

Lebanon’s majestic cedar forests are the country's national symbol. Yet the famous forests and the animals that live there have declined precipitously as the result of logging, invasive species, human encroachment and hunting.

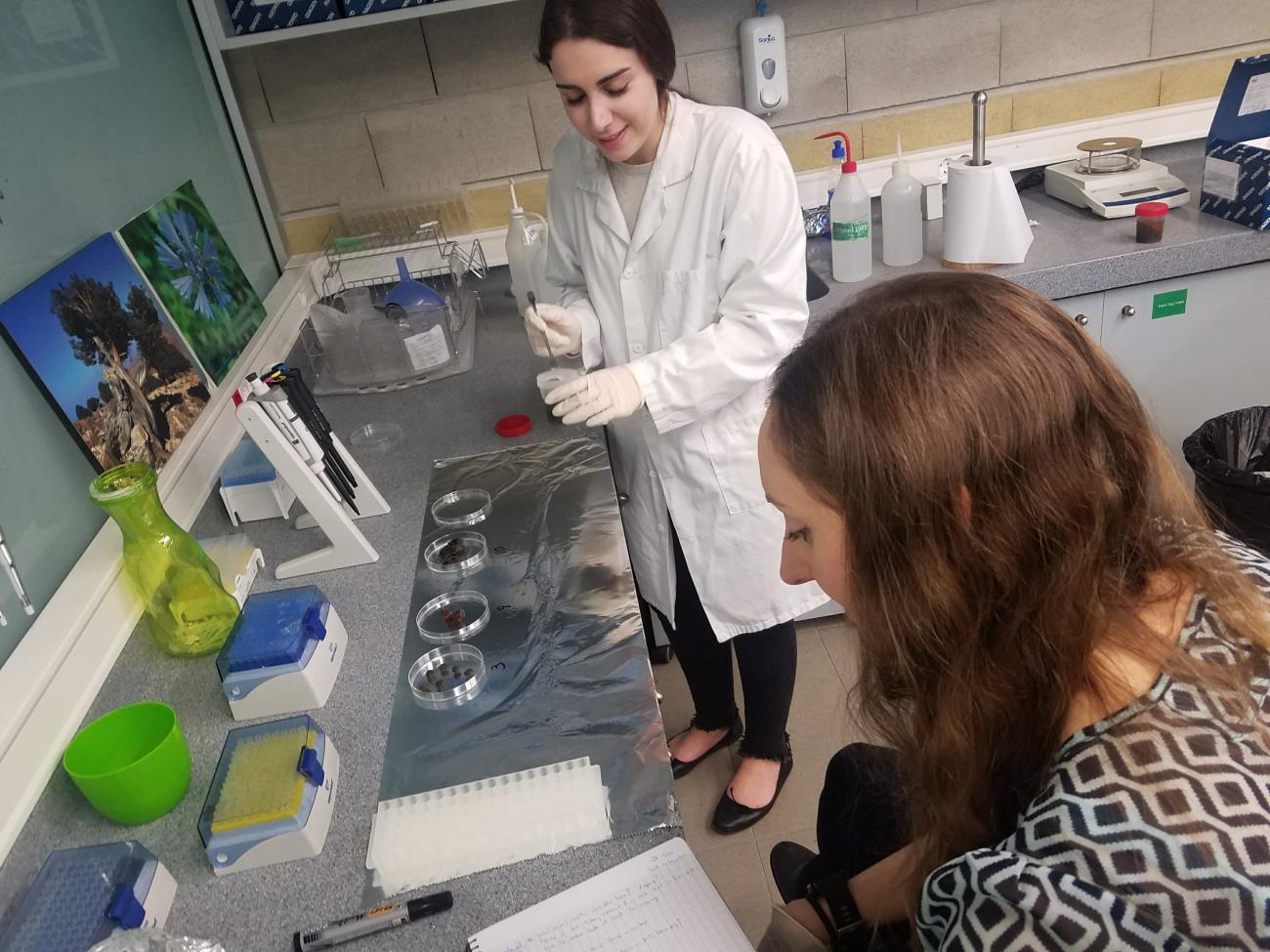

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s (SCBI) Center for Conservation Genomics (CCG) Lab Manager Nancy McInerney and graduate student Lilly Parker traveled to Beirut in November 2017. There, they met Dr. Magda Bou Dagher Kharrat at St. Joseph University in Beirut and helped train her graduate students in DNA metabarcoding. This tool will help Magda and her team identify wildlife in the cedar forests and learn how the animals help disperse plant seeds. Ultimately, what they discover will inform a plan to conserve the plants, animals and forests overall.

What prompted your visit to Lebanon?

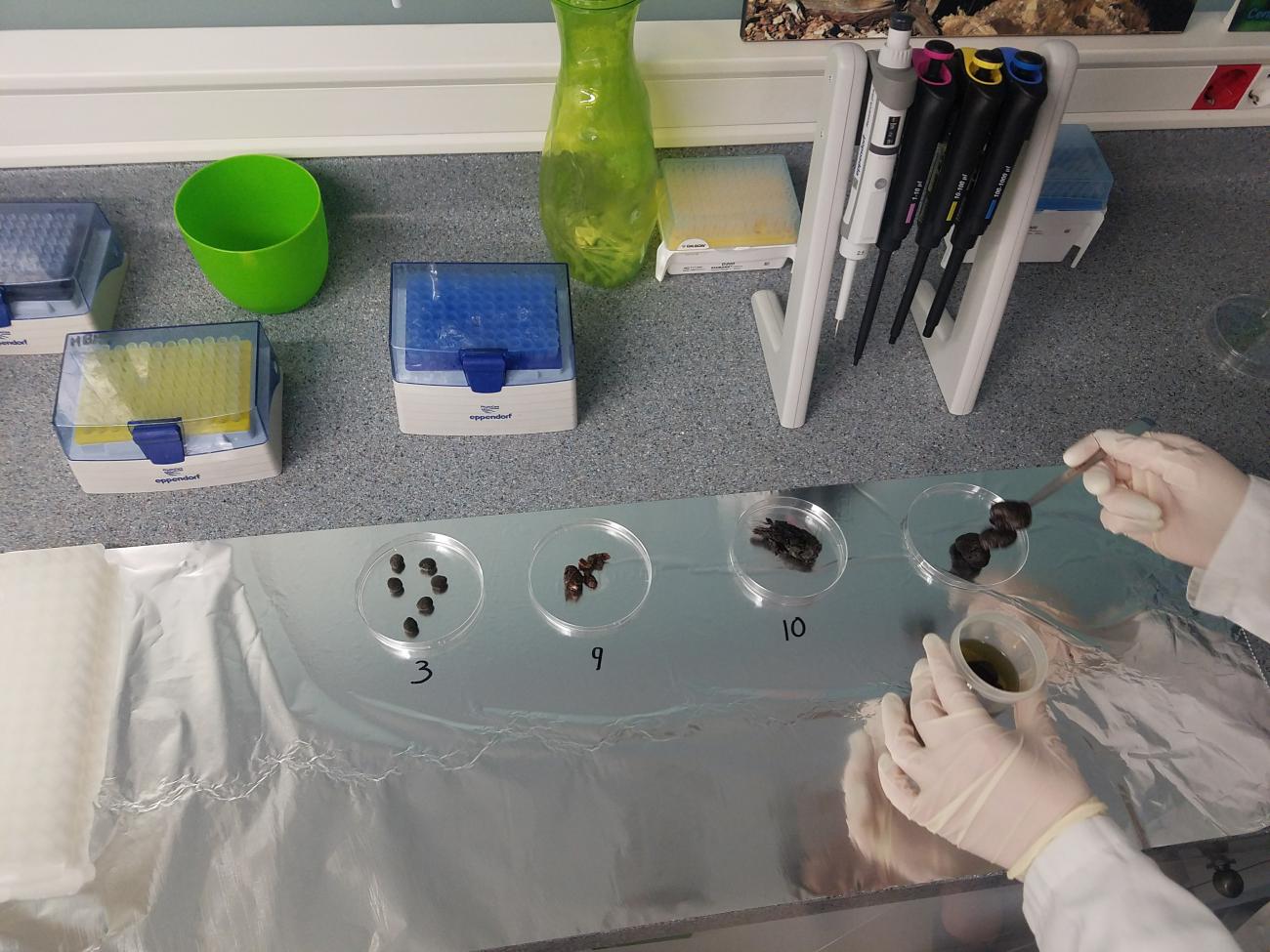

McInerney: In March of 2016, Magda came to visit our lab to see how SCBI uses metabarcoding. Metabarcoding is taking a sample, like scat, and amplifying and sequencing different DNA to get information from it. For example, by analyzing a single scat from an animal, we can figure out which species it is, determine what it ate and look for any signs of disease, etc.

In Magda’s lab, she and her graduate students are picking up scat samples in the forests of Lebanon to determine what animals are in the forests, what they are eating and if they are dispersing plant seeds. She asked if we would come to her lab to help move their project forward.

I have experience starting a lab and Lilly has experience with mammal barcoding. In addition to working with Magda and her students, we gave a public lecture about CCG’s conservation genomics research and did an in-depth course for master’s students on metabarcoding.

How will DNA metabarcoding help conservation efforts?

McInerney: Conservation starts with knowing what animals are present. If we do not know what is there, we cannot conserve them appropriately. With the few samples they have collected so far, we found wolf, marten, wild boar and hare. In addition, by knowing what the animals are eating, forest managers have a better sense of the dynamics in the forest and which animals and plants to conserve.

Magda will also be doing germination experiments that will help guide the tree nurseries in growing those plants for a head start before planting them.

Parker: Magda has begun training forest managers—many of whom do not have backgrounds in biodiversity and conservation—about the plants in the forests. DNA metabarcoding will help her train them and members of the public about the forests’ animals and how to recognize these animals through the scat and paw prints they leave behind.

The ultimate goal is to raise awareness and help the public to take pride in their native animals, instead of seeing them as a threat or food source.

Did you go into the legendary cedar forests?

McInerney: We were able to visit two forests, which were beautiful and quiet. These cedar forests include plants that do not live anywhere else. Although we did not see or hear any animals, we found many scats just by walking around for a couple of hours. Coming back to Washington, D.C. gave us a real appreciation for the difference—here we see squirrels, birds, foxes and deer in Rock Creek Park. Despite our urban sprawl, we still have animals, and the Lebanese want to see their native animals, too.

Parker: They do not know what mammals are still living in the forests because of poaching and lack of infrastructure to study the mammal communities. Historically, the forests have been home to hyenas, wolves, wild pigs and all kinds of small carnivores.

Before the biologists enter the forest to plant seedlings, they have to sweep for mines. It was eye opening that they have to deal with warfare before they start their conservation efforts.

What did you teach the students?

McInerney: They wanted to know the best way to keep track of their samples because, with metabarcoding, it can get complicated. You have one source, one animal scat that you collected in one forest on a certain date, but you get so many different kinds of information from that one sample. We taught the students how to organize the data effectively, which will help ensure that they are successful with the metabarcoding work.

Parker: Magda’s grad students have all of the enthusiasm and the know-how to do this work. We just gave them a boost into this next-generation sequencing world.

What are the next steps for this collaboration?

McInerney: We will continue to collaborate with Magda and will likely be involved in helping her analyze the data. We are hoping she will return to our lab this year to learn ancient DNA methods.

They do not have a natural history museum in Beirut, which means they do not have a reference source for the animals that were once there. A monk in the very north of Lebanon started collecting and performing taxidermy on animals in 1976, though he did not have a scientific background. He converted his school to something like a museum. Magda is hoping that she might be able to use this collection to do some ancient DNA work to get a more complete picture of the animal community historically in Lebanon.

This story was featured in the January 2018 issue of Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute News. This trip was funded by Farmer to Farmer, a USAID-funded program through Land O’Lakes International that supports farmers in other countries with technology transfers, including farmers working in agriculture and forests.